Market Overview

The Debt Threat

While most Americans welcome the recent tax cuts, but there is one nagging, little problem: the deficit.

This isn’t like the 2001 tax refunds, when George W. Bush essentially mailed out rebates because the federal government had collected more money than it needed. Instead, the budget deficit was already up to 12 digits when Donald Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

The 2017 federal budget was $4.0 trillion, and the deficit was an ominous $666 billion. The 2018 budget actually trims spending marginally, but there is no way of knowing what the deficit will end up being. We know the President asked for $440 billion more in spending than in projected revenue, but we also know he overspent last year’s requested deficit by almost a third. If that occurs again in 2018, we can expect a deficit well in excess of half a trillion dollars again.

But it could be far higher. Based on year-to-date overspending, Forbes expects the deficit to exceed the year-earlier figure, and approach or exceed $1 trillion in 2019 then continue to expand going forward. And tax reform is expected to reduce total inflows by $1.6 trillion over 10 years while the recent omnibus bill keeps spending authority at 2017 levels. In short, this has been a terrible year for deficit hawks. Each year’s deficit just adds to the total outstanding public debt, which now stands at $21 trillion. That’s half a trillion higher than it was on New Year’s Eve 2017, which was half a trillion higher than it was on Inauguration Day. You’ve heard that big, scary number in any number of stump speeches, sound bites, talking points, and other Beltway blather.

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, Federal Reserve

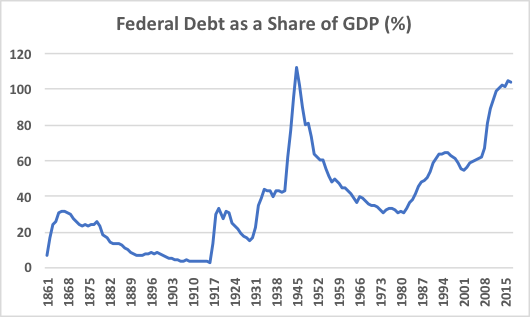

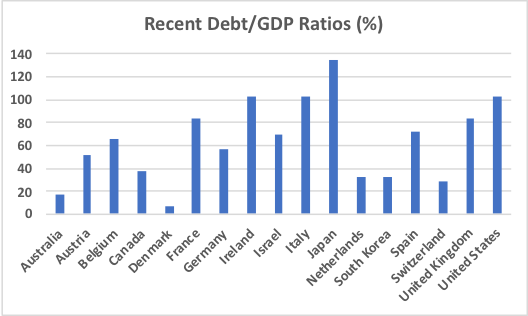

But here in the financial community, numbers in isolation – no matter how huge – don’t mean much to us. We can only understand them in comparison with other numbers, so we look for ratios. In the case of debt, we like to compare it to the country’s gross domestic product – basically, the size of the whole economy. By that measure, U.S. debt is about 104% of GDP. Is that too high? For guidance on that, there are two places to look: U.S. history and the rest of the world today.

Looking backward, the current debt is fairly high, but debt to GDP ratios were similar at the end of World War Two. Taking a glance at countries with roughly the same standard of living as ours, we see that most are lower, but Ireland and Italy are on a par with the U.S. now and Japan has a much higher ratio than we do.

Source: International Monetary Fund

Nobody wants to owe a lot of money but if you, like many readers of this column who have a mortgage, then you know that not all debt is bad. So what’s wrong, practically speaking, with running a big, persistent deficit?

It’s not the debt itself that’s bad. It’s the interest owed on that debt that has to be considered, and interest rates are poised to rise.

In Barack Obama’s first term, the debt ballooned to fund a $700 billion financial bailout and an $825 billion stimulus. But the interest rates in early 2009 were amazingly low. The yield on the 10-year T-bill was a meager 3.2%. One could argue that the Obama administration would’ve been negligent not to borrow as much essentially free money as it could.

The 10-year yield is still in that neighborhood, but it is bound to rise for two reasons: 1) the Fed has made every indication that it’ll keep raising the linchpin Fed Funds rate, and 2) the higher the government’s debt in relation to its income, the higher the yields investors will demand in order to lend to it.

You have some decisions to make. Is it time to reconsider your percentage allocations to stocks and bonds in anticipation of better yields with lower risk? Should you refinance your home now before rates spike? Is it time to rebalance your portfolio in anticipation of higher inflation, or in anticipation of another full-blown recession? It might be time to talk to your financial professional.

Maybe we don’t get our money’s worth out of our tax dollars, but we do get something: national defense, a justice system, parks, public works and so on. We get nothing at all out of paying interest. We all want the government to siphon off less of our hard-earned money, but wouldn’t it be a shame if we have to take everything we saved from having our tax rates lowered, and pay it out for higher rates to pay off our homes, cars and educations?