Market Overview

This month's models have been posted.

The Even-Greater Recession?

Remember when George W. Bush enacted the Troubled Asset Relief Program, handing the banks $475 billion to paper over their bad debts – and how shocked you were that taxpayers were expected to bail out Wall Street? Remember just a few months later when Congress gave Barack Obama his American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, and how we all balked at the $800 billion we were expected to spend on make-work projects?

Before the all-clear is sounded on the Covid-19 pandemic, a Republican president and a Democratic speaker whose mutual animosity could not be clearer – plus a Republican Senate majority leader who has reveled in passing as little legislation as possible – will have joined forces to enact emergency spending bills that more than double the 2008-2009 package.

But the Great Recession wasn’t the first time – and the Coronapocalypse won’t be the last time – that Washington applied its fiscal and monetary muscle to stimulate the economy.

Aside from the sheer magnitude of the 2020 price tag, nothing is really new, nor is any of it particularly partisan.

2020 stimulus vs. 2009 stimulus: More money, but maybe less outrage. Credit: CNN

The cash cure

If you ask Americans when did the U.S. government first use stimulus packages to spend its way out of economic straits, many would answer the 1930s – Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal. But that’s the wrong Roosevelt, and the wrong deal. In 1902, Theodore Roosevelt began striving to find a Square Deal between capital and labor. Among other things, he funded irrigation projects and similar public works, while giving away Midwestern farmland. In response to the Panic of 1907 – triggered by liquidity issues at the nation’s depository institutions – the Square Deal gave banks the right to issue their own emergency currency backed by whatever assets they had on hand, rather than by precious metals only. And TR’s program also put wages owed ahead of bondholders’ claims in the event of corporate bankruptcy – which apparently wasn’t the case prior.

But Cousin Franklin was certainly more aggressive in his approach. Then again, he did have a deeper pile to dig out from under. One of the first things FDR did was pour the equivalent of today’s $60 billion into creating minimum-skilled, minimum-paid jobs. He followed up with establishing Social Security, farm subsidies and federally chartered deposit insurance— programs that remain in place to this day. Harry Truman expanded many of these programs incrementally as part of his small-bore Fair Deal. Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society matched the New Deal’s use of federal money to reshape the economy but, considering that annualized gross domestic product got as high as 8% in the mid-1960s and wages were going up around 5% annually, you could hardly call LBJ’s agenda a “stimulus”.

The check is in the mail

Bush 43 doled out free money in 2001, and that wasn’t exactly a stimulus either. Unsurprisingly, the tax rebate provision of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act was immensely popular.

It was great politics, but not great economics. Not all stimulus packages work equally well and, in general, none are ever optimal. Even FDR’s famed Works Progress Administration – which turned the federal government into America’s largest employer – was more theater than substance. While such public works projects as Hoover Dam are marvels of lasting value, there was also a lot of frivolous waste. It would’ve been more efficient to just hand everyone without a job in 1933 an envelope full of cash.

The Bush tax rebates, though, were truly regrettable when viewed through a long lens. First, the timing could’ve been better. The dotcom bubble had burst, and it looked like the country was heading toward recession. Giving each family $600 could help assure a softer landing perhaps, but then September 11, 2001 became the generation-defining event and the economy went into a much steeper, though short-lived, decline. Those rebate checks, which most recipients put in their bank accounts, either stayed there or were used to pay a post-9/11 utility bill. Very little excess spending was prompted by them.

Making matters worse, September 11, 2001, was followed by April 15, 2002 – the date when America found out that the rebate check was considered taxable income.

Which brings us to …

The Covid-19 relief package is really a suite of three – and soon to be four – acts. The first was a modest $8.3 billion emergency appropriation to help pay for vaccine development, public health access and medical supplies. The second was an even more modest provision to pay for coronavirus-related sick leave and family leave, supplement unemployment benefits and increase funds for food assistance.

But the third time is the $2.2 trillion charm. Roughly one-third of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act consists of loans to businesses large and small which will almost certainly be forgiven. There are some set-asides for the airline and air cargo industries and even a little for public transit. Another half-billion dollars is indirect aid funneled through the states, Veterans’ Administration and other channels. Of the rest, $221 million is a write-off of tax receipts that just aren’t coming.

But that doesn’t quite get us to $2.2 trillion. There are two other CARES provisions, both of which have gotten more press than the others. First, $250 billion is set aside to expand unemployment insurance. Clearly, we’re heading for unprecedented job losses, and this fund adds another $600 per week to laid off workers. It similarly pays $600 to freelancers and gig workers who, by dint of not paying into the unemployment insurance fund, have generally never received this benefit before.

But CARES’s public relations tentpole is the tax credit, which will take the form of checks or direct deposit to – if things go according to plan for once – all qualified adults. There are ceilings that kick in for adjusted gross income over $150,000 for joint filers, $112,500 for a head of household or $75,000 for a single person, but every other adult citizen gets $1,200 plus another $500 for each dependent child who has not yet turned 17.

There’s more to it, and NPR offers an excellent recap.

Lessons learned, if any

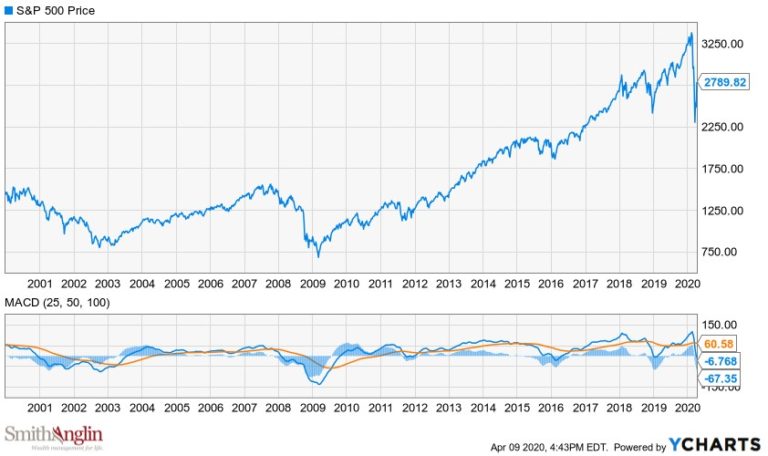

You know how we told you in this space that you often don’t know if you’re in a recession until you’re about six months into it? While that holds for the bottom of a normal business cycle, this is a self-induced recession resulting from a true “black swan” event. It’s safe to say, then, we’re in a recession now, and there’s no need to wait until next flu season for confirmation. So, we’re in a rare position to take steps in real time that could actually mitigate the effects.

To that end, Democrats in the House of Representatives are preparing another stimulus package – with a $1 trillion-plus price tag on top of what’s been earmarked already – and President Trump has signaled support for at least some of the provisions. This will expand CARES’s small-business lending while extending the length of time people will be eligible for unemployment insurance and tax credit payments. Aid to small cities and towns is on the table, as is greater support for healthcare providers and corporations operating in sectors of the economy hardest hit by the shelter-in-place lockdown.

One lesson Congress actually managed to learn from all this is to not let the perfect – defined however you like – be the enemy of the good. Both Republicans and Democrats had pet projects they’d have loved to shoehorn into an 800-page, $2.2 trillion omnibus. And any individual senator of either party could’ve thrown a temper tantrum and derailed the whole process. That didn’t happen.

Another lesson is that conventional economic wisdom is not always backed up by hard economic evidence. For example, the presumption that paying people to do nothing means they will tend to do nothing has been pretty much abandoned on both sides of the aisle. In the current case, people are idle because their employer closed doors, often at the direction of their state governors. They’re getting money because they’re out of work, not out of work because they’re getting money. To argue otherwise is like suggesting that having access to dentists causes cavities. When all this is over, a lot of people will have a renewed appreciation for the sense of purpose and camaraderie provided by the workplace.

One lesson from the Bush tax rebate experiment remains to be learned, though, one which was first theorized by the conservative movement’s own Professor Milton Friedman. Among his seminal concepts was the “permanent income hypothesis”, which suggests that consumer demand stems from the individual’s expectation of permanent, periodic income, not from a one-off stimulus check. According to Friedman, a one-time check is likely to end up in a savings account or will be used to pay down current debt. For the CARES $1,200-per-grownup / $500-per-kid formulation to have its desired effect of buttressing demand, Friedman would say, people need to know that there will be more money coming in the door the next month, and the month after that, and for years to come.

That’s the thinking behind the Universal Basic Income (UBI) proposal we discussed in this space last year. As a one-time payment, the CARES rebate isn’t true UBI. Still, it’s perceived as such by those who see it as money for nothing (also referred to as “helicopter money”). And yet, many people who were critical of the proposal made by Andrew Yang in 2019 have less issues with the proposal made by Mitt Romney in 2020, which was passed unanimously by the Senate controlled by Mitch McConnell and signed into law by Donald Trump.

That said, one lesson was learned from the Bush rebates: Don’t tax it. The CARES rebate, at least, is tax-free.

Uncertain future

But there’s reason to hope that one lesson learned from all this is that the nation – and its economy and its government – function best when there’s unity of purpose, such as the kind engendered by a calamity such as the coronavirus pandemic.

Maybe we’ll all be better for having gone through this together. But maybe, by the time hockey season starts, all this will be over and we’ll all go back to our corners. Whatever the outcome, it’s best to be prepared for any contingency. Now, more than ever, it’s critical to talk to a financial professional about what the incipient recession and the stimulus package passed as a result mean to your family’s financial future.

Steve Anglin, CPA is a Managing Partner at Smith Anglin Financial, and the Head of the Tax Preparation Services. He is also responsible for Smith Anglin’s compliance supervision. He holds a BBA in Accounting and a BBA in Real Estate, and numerous securities licenses and designations.

Steve Anglin, CPA is a Managing Partner at Smith Anglin Financial, and the Head of the Tax Preparation Services. He is also responsible for Smith Anglin’s compliance supervision. He holds a BBA in Accounting and a BBA in Real Estate, and numerous securities licenses and designations.