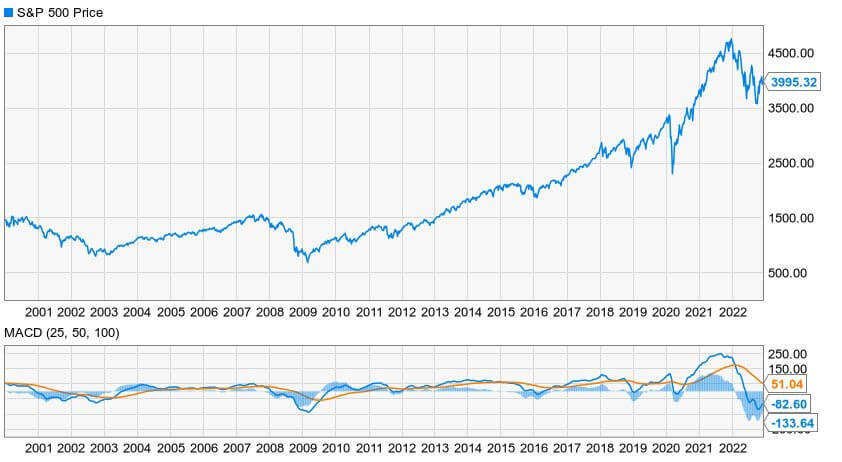

Market Overview

This month's models are now available. There are CHANGES in ALL THE MODELS.

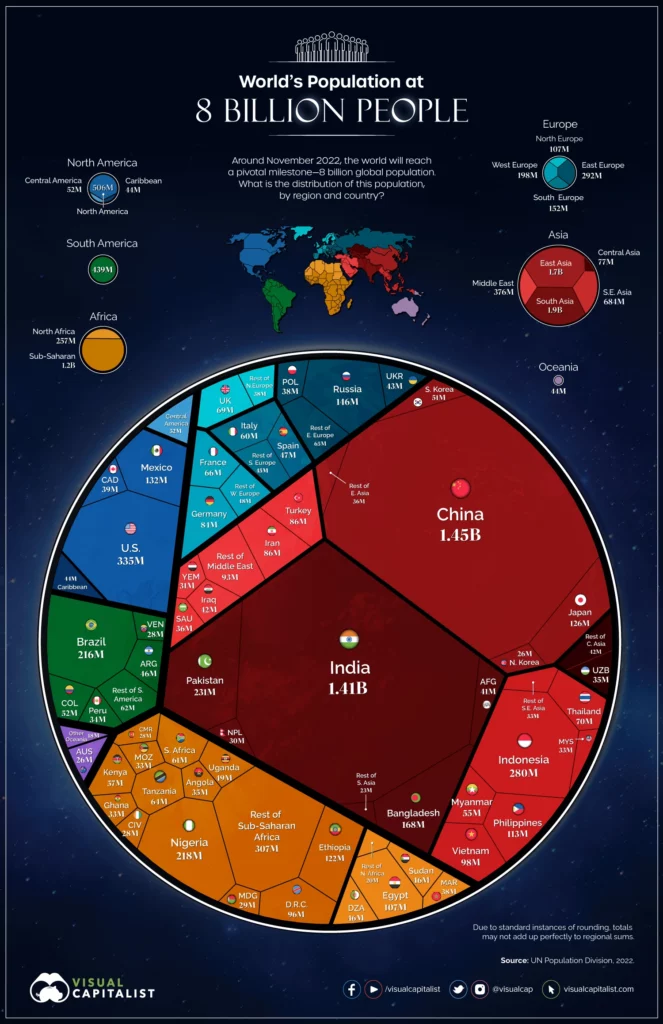

Population: 8 billion and counting

Last month, the human population of the Earth surpassed 8 billion. These people all need food, shelter, clothing and – no joke – cell phones. More than 9 out of 10 people worldwide have these devices.

Can the Earth’s bounty sustain such a census? Can demand keep up with supply? Yes, probably, but it’s going to take increasing technological advancement and entrepreneurial innovation.

We’re still bigger than Indonesia, but maybe not for long. [Credit: Visual Capitalist]

‘The surplus population’

With a nod to the Season, let’s take a quick look at Charles Dickens’s most enduring novel:

"At this festive season of the year, Mr. Scrooge," said the gentleman, taking up a pen, "it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the Poor and destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts, sir."

"Are there no prisons?" asked Scrooge.

"Plenty of prisons," said the gentleman, laying down the pen again.

"And the Union workhouses?" demanded Scrooge. "Are they still in operation?"

"They are. Still," returned the gentleman, "I wish I could say they were not." …

“I help to support the establishments I have mentioned--they cost enough; and those who are badly off must go there."

"Many can't go there; and many would rather die."

"If they would rather die," said Scrooge, "they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population. ..."

A Christmas Carol was published in 1843. Although the economist Thomas Robert Malthus had died about nine years earlier, his famous work, An Essay on the Principle of Population, which predated Scrooge’s story by almost 50 years, was still very widely known and accepted. In a nutshell, Malthus argued that all this Enlightenment optimism was pure claptrap because the population was growing far faster than the ability to grow food. By this thinking, the future would be a bleak hellscape of rampant starvation – what economists have come to call “the Malthusian catastrophe”. The way to prevent this, Malthus argued, was to stop giving money to disease prevention or hunger relief charities – better to kill off two mouths to feed than the inevitable 20 or 200 or 2 million.

Malthus was, as it turns out, dead wrong. True, England in the 1790s was turning out babies faster than it was turning out arable acres. But that was one place in one time. All we need to do to disprove Malthus is to point out how much land outside of England – entire continents! – was available for agriculture. Of course, we’re near the exhaustion point now, but there are other things Malthus didn’t consider: agricultural technology advancements, food processing improvements stemming from the Industrial Revolution, preferences for smaller families and a slew of other counterarguments.

Ultimately, Malthus’s argument collapses on this point: When he was writing, the world’s population hadn’t yet breached 1 billion. Here we are, 200-plus years later at 8 billion and we’re complaining about the price of chicken going up 15% in a year, rather than wrestling over the last drumstick.

World class

The erstwhile “population explosion” has slowed down of late. According to the United Nations, the growth rate has fallen below 1% for the first time since 1950. We’re not likely to hit 9 billion for another 20 years, and probably will never get to 11 billion.

Still, where all those babies are being born continues to shift. If India hasn’t already passed China in terms of population, it will within the year. More than half the world’s population growth between now and 2050 is projected to come from just eight countries. In addition to India, these include Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines and Tanzania.

And while many parents in post-industrial countries tend to favor one-child households, developing nations still have large families, and this puts a burden on health and education programs.

While families in wealthy nations are delaying birth, pretty much everybody everywhere is trying to delay death. Global life expectancy is now 72.8 years, a nine-year improvement since 1990. This, of course, also impacts health care and requires societies to put more money in place for pensions.

In between birth and death, there’s a lot of moving around. As many as 61 countries report populations declining by at least 1% per year and, while lower birth rates are part of that statistic, the rest is net emigration.

“Over the next few decades, migration will be the sole driver of population growth in high-income countries,” according to the UN report, World Population Prospects 2022.

While questions of national identity will continue to be highly emotional, the fact remains that developing countries are where the working-aged people are, and the wealthy countries are where the retirees are. Something’s got to give.

Some migration is driven by economics, some if it by survival. Around the world, economic migrants tend to come from the countries of south Asia or from economically mismanaged countries such as Venezuela. Meantime, millions are fleeing conflict in Syria, Myanmar and other war-torn nations.

Narrowing our focus to just the United States, Mexico accounts for one out of every four immigrants, according to the Pew Research Center. Even so, more U.S. immigrants come from Asia as a whole than from Latin America. Surprisingly, almost half of all U.S. refugees are from the Democratic Republic of Congo, followed by Myanmar and Ukraine.

Pew’s study finds that three-quarters of immigration into the U.S. is legal, but that still leaves roughly 11 million unsanctioned foreigners living in the U.S., mainly in California and Texas. The Migration Policy Institute finds that almost half the immigrants here illegally are from Mexico; if you sum the total from Mexico, Central America and South America, it adds up to around 8.6 million people.

We are the world

Another thing Malthus got wrong is the cause of economic distress. If someone was poor, Malthus believed it was Divine punishment for laziness or the pursuit of vice. That thinking persists to the present day. In such a land of opportunity as America, character flaws go some of the way of explaining the roots of poverty, but not the whole way. Even here, we need to also consider an individual’s family responsibilities, mental health, physical disability and a myriad of other factors. In places where similar opportunities simply don’t exist, poverty is just the default condition.

Someone with the brains of Thomas Edison or the vision of Steve Jobs or the sheer determination of Elon Musk is born every day in the Southern Hemisphere. They might never be able to turn their potential into action, though, if they can neither put their plans in motion in their home country nor emigrate to another that would give them a fair shot. And for every one of those rare individuals, there are hundreds if not thousands of people who could pick up the basics of air conditioner repair or medical record keeping or Python programming.

And that’s where Malthus really fails. These people have worth – not just in the metaphysical sense, but in the economic sense. Some have what it takes to create the next trillion-dollar company. Others have what it takes to do skilled work that would pay them a living wage.

Fortunately, there are ways to not only give these people a chance to realize their dreams, but to actually profit by investing in them. When you’re thinking of diversifying your portfolio, think about which regions or specific countries you’d like to invest in – and why. Is it the growing consumer spending power of its middle class? Is it active in an industry in which you predict rapid growth? Is there resource wealth that has yet to be extracted? Does it offer government policies that you believe will allow it to develop faster than its neighbors?

All good reasons but, before you place specific bets, it’s a good idea to discuss the wheres and whys with a trusted financial advisor. Please read the column at the end of this newsletter for some points of discussion.