Market Overview

The New Protectionism: Who Does It Help? Who Does It Hurt?

The United States recently imposed tariffs on solar panels and washing machines from China, a move likely to drive up the prices of these goods. Although their American manufacturers will probably see increased unit sales and revenues, U.S.-based makers of other products that ship around the world might not share that wealth because other countries could retaliate with trade barriers against U.S. wares. It could get ugly.

But that does not mean it absolutely will get ugly. The reality is more nuanced.

The Trump Administration obviously does not believe free global trade is always in America’s domestic interest. It walked away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and is currently going to the mat renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement. Both trade deals would allow trading partners to derive mutual gains by specializing in making certain products, building efficiencies to create a competitive advantage, then exchanging those products with countries that are better at making other things.

Economists from across the political spectrum – and just about anyone who had ever sat through their college econ classes – were certain that these isolationist tactics were terrible ideas. The conventional wisdom goes, tariffs protects domestic businesses that are simply no longer competitive on the world stage, causes a retaliation from countries that can no longer sell their goods here and passes higher prices on to the American consumer.

And yet the sun still rises.

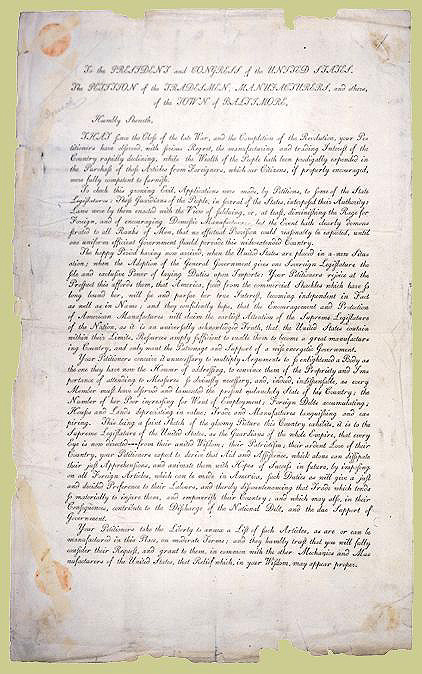

The History Lesson. The first thing the U.S. federal government ever did – within four months of George Washington’s 1789 swearing-in – was to enact tariffs. The purpose then, as now, was twofold: protect industries and raise revenue. While it was a rallying cry of the Boston Tea Party, as soon as that representation was in place, America levied 17 separate subparagraphs of import taxes on tea.

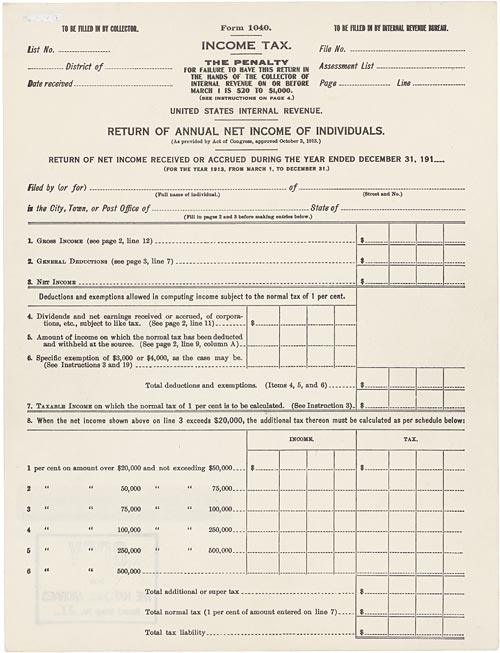

For a very long time, tariffs were simply the most efficient way for governments to raise money. After all, there were millions of employed workers and only a couple dozen ports. Taxing citizens’ income was inconceivable until just over a hundred years ago.

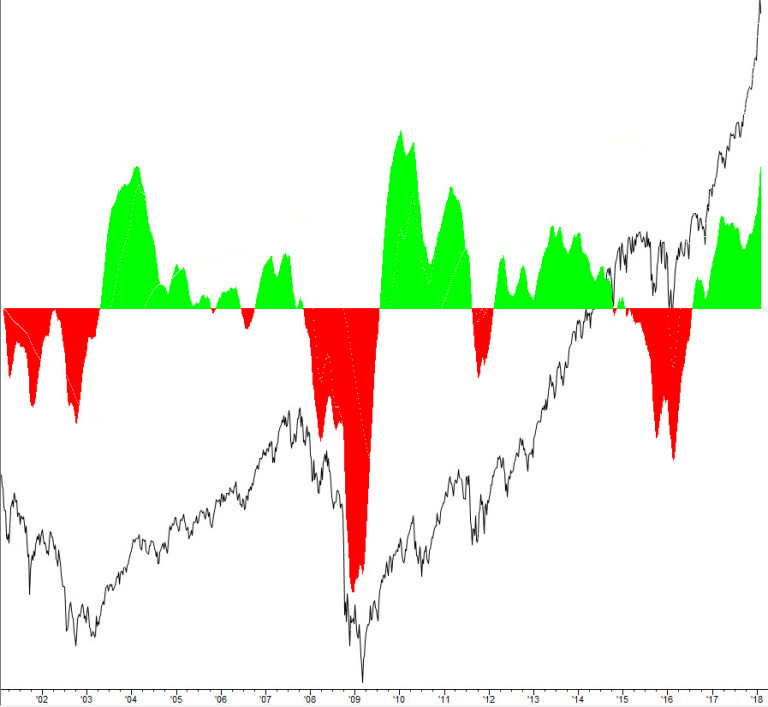

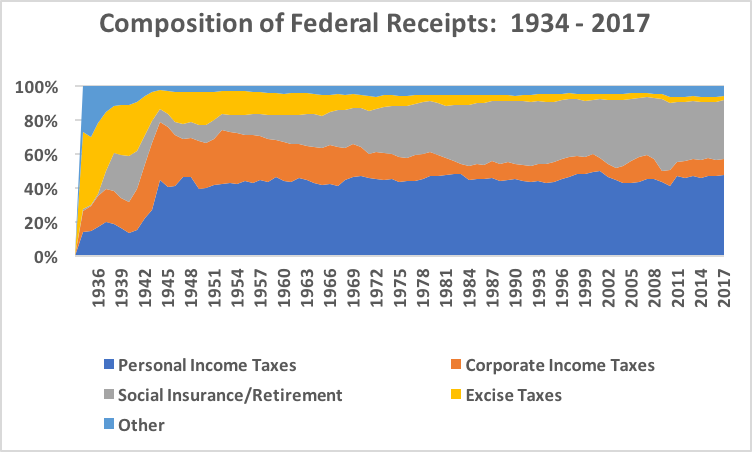

And even once the genie was out of the income tax bottle, that did not stop the federal government from swigging out of the tariff bottle. As late as 1950, one dollar out of every five sent to Washington fell under the rubric of “excise taxes,” in which duties were lumped in together with cigarette, alcohol, gasoline, and air travel taxes. Today, it is less than one dollar out of every 30.

source: Office of Management and Budget

What changed? It was America’s consensus on free trade. At that point in time, Fort Knox held roughly 70% of the gold bars in the world. The dollar was on the gold standard, and every other major currency was pegged to the dollar. Due to its geographic remoteness from the battlefields of World War Two, the contiguous United States also held most of the world’s intact industrial capacity, and, due to its comparatively late entry, it further held an advantage in terms of healthy workers, productive talent, and skilled managers. With no real economic rivals, Americans developed tastes for imported goods, and there was little fear of anyone losing their jobs to foreign competition. Through most of the 1950s and 1960s, unemployment remained below its natural long-term rate. That is to say, there was a labor shortage.

As increasingly affluent Americans shrugged off gradual rises in income tax, tariffs fell out of favor. Of course, any country wants to protect some of the key, strategic industries that serve as the lynchpins of its economic or military power; it is much the same reason why, as inefficient as the process may be, paratroopers tend to pack their own chutes. As recently as 2002, President George W. Bush imposed a steel tariff of up to 30%, which was rescinded after about a year and a half.

As in 2002, the White House is responding to what it perceives as companies from other nations “dumping” cheap imports into the American market, with the implication that their governments are giving them tax breaks, subsidies, or other price supports.

Of course, no one can say with a straight face that solar cells and washing machines are as integral to the U.S. economy as steel has long been, but the cases have their parallels. Mr. Bush’s move was made in reaction to what could reasonably be interpreted as aggressive pricing on the part of Asian steelmakers. By the way, that pricing was already years in the past, and stability had returned to the market. That said, the dumping did have its presumably intended effect of forcing many American steel firms into insolvency. The duty was introduced as a temporary measure to give U.S. factories room to reorganize.

The agency responsible for taking action is the U.S. International Trade Commission. Businesses that believe they have been harmed by unfair trade practices complain to the ITC which investigates and, if merited, reports its findings to the U.S. Trade Representative, who works out of the White House.

And, as was the case 16 years ago, the ITC sees a problem that the global watchdog World Trade Organization does not. Specifically, Whirlpool alleged “serious injury” because of “an aggressive downward pricing policy” on the part of South Korean appliance makers LG and Samsung. Whirlpool first raised the issue in 2011, and, when the ITC clamped down on Korean washers, production shifted to China. When the ITC then acted against China, the whack-a-mole game moved production to Thailand and Vietnam. Country-specific sanctions were not working, so last month the ITC imposed duties of up to 50% on imported washers from anywhere, period.

We have known the Beijing government has been subsidizing its solar cell producers since 2011. According to the U.S. Trade Representative, “those producers were selling their goods in the United States for less than their fair market value, all to the detriment of U.S. manufacturers … By 2017, the U.S. solar industry had almost disappeared…. Only two producers of both solar cells and modules, and eight firms that produced modules using imported cells, remained viable. In 2017, one of the two remaining U.S. producers of solar cells and modules declared bankruptcy and ceased production.” That sole survivor, Suniva, filed for action and has been handed a 30% tariff by the Trump Administration.

While there are benefits to protectionism, it does not mean that the costs are to be ignored. For instance, it is estimated that the 2002-2003 steel tariff had the unintended consequence of costing America 200,000 jobs. The astounding part of that figure is that there were only around 187,500 steelworkers in the country at the time. According to the CITAC Foundation, the effect of higher steel costs rippled into the fabrication, machinery, transportation equipment and other industries.

If that happens this time around in industries adjacent to solar panels or major appliances, the economic and political repercussions could echo for a generation.