Market Overview

This month's models have been posted. There are NO CHANGES in any of the models. The rest of the newsletter will be posted by mid-month.

Self-driving cars don’t drive the market

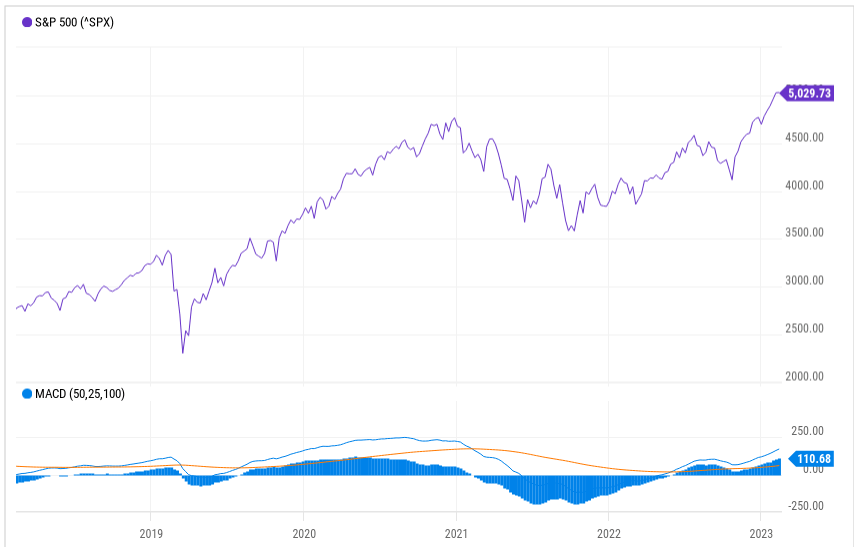

You can’t tell from the Nasdaq index, but a lot of leading-edge technology companies aren’t making money. Even though the Nasdaq, a tech-heavy stock price benchmark, soared 43% in 2023 – far outperforming the Dow and S&P 500 indices – self-driving vehicles have stalled, electric vehicles are on the fritz, and artificial intelligence still hasn’t overcome natural skepticism.

It’s anyone’s guess when we’re all going to have the jetpacks promised to us in the old Popular Mechanics issues, but it also might be a long time before we have a carbon-neutral sedan that can both drive on its own and read a map.

‘Tokyo, we have a problem …’

The emblem of our present stumble into the future might as well be the Hakuto-R, Japan’s first lunar lander, which crashed into the Moon at almost 4,000 miles per hour.

A generative photo of everything that’s wrong with the Tech sector. At least AI is good for something. Credit: Rahul Gupta, India Today

One thing that makes this a good metaphor is that it was just the first in a series of unanticipated slip-ups. Hakuto-R met its violent end in April 2023. Despite destroying itself and its payload on impact, the mission was considered 80% successful; it was in lunar orbit doing science-y stuff for five months before the crash.

And that was good enough to greenlight another moonshot. This just happened last month and is probably the one you were thinking about: The Smart Lander for Investigating Moon. On January 19, SLIM made Japan the fifth nation to land softly on the lunar surface.

And the first to do it upside down. That part, of course, was unintended but, as a result, its solar cells were oriented in the wrong direction and there was little hope of it surviving after its batteries drained. A week later, as luck would have it, there was just enough power to point the cells toward where there was just enough sunlight for it to recharge. It’s working again.

So, the metaphor holds: Failure leads – with time and a little good fortune – to success. And that may be fine if you’re a university or government entity doing pure research. But that’s not the story the venture capitalists want to hear. SLIM’s business proposition includes – in addition to proving that Japan is getting better at lunar landings – prospecting for a mineral called olivine which could help scrub carbon dioxide from Earth’s atmosphere. The presence of olivine also suggests the presence of other minerals with other uses. SLIM, sometimes called “the Moon Sniper,” also unloaded a couple of lunar rovers that will help survey previously unexplored parts of the lunar surface.

Still, there’s plenty of olivine here on Earth. It might be hard to get to, but it’s got to be easier than flying it back from the Moon. This really does look like someone’s gone to the Moon’s Sea of Nectar on a fishing expedition.

Closer to home

Here on humanity’s origin planet, self-driving vehicles are stuck in Neutral. The first prototypes came out in the mid-1980s and, 40 years later, it’s at what software engineers call “Level 2” of development – out of five levels. Eva Mo, who’s working on the problem for chipmaker Nvidia, projects another decade before self-driving taxis, full-assist consumer vehicles and autonomous trucks are past Level 3.

Meantime, self-driving taxis are not making a great case for themselves. Cruise, General Motors’ entry in the space, faces regulatory scrutiny following an October 2, 2023, accident in San Francisco. According to IoT World Today, “a pedestrian was struck by a human-driven Nissan, which propelled her into the path of the Cruise autonomous vehicle. She was then dragged 20 feet, worsening her injuries, as the self-driving taxi failed to come to a halt, attempting a pullover maneuver.”

This is just the latest example in a string of fatalities that dates back to 2016, when its “Autopilot” function put a Tesla Model S in the way of an oncoming truck, killing its human occupant (can’t really call him the driver).

The self-driving taxi operations aren’t standalone companies but rather divisions of deep-pocketed companies: GM’s Cruise, Alphabet’s Waymo, Toyota’s May Mobility, Amazon’s Zoox, Baidu’s Apolong and Hyundai’s Motional. This suggests there’s a long way to go before the segment is profitable.

The broader assisted auto market has more of a startup vibe: Pony.ai and Mobileye are developing features that can be bolted onto legacy vehicles, alongside such giants as Nvidia.

The value proposition for this class includes improved safety, reduced traffic congestion, increased accessibility and energy efficiency – as well as the big one: making the commute less of a chore. That’s why McKinsey sees this as a potential $400 billion per year market – if you’re willing to wait until 2035.

Plug ‘n’ pray

This is all developing in parallel with electric vehicles.

We tried this before – a hundred years ago. EVs failed then and they’re barely scraping by now. While we tend to accept the inevitability of EV pervasiveness, we don’t believe it’s going to happen in the short run. Despite all the SPAC money that flowed into this segment over the past few years, there have been few winners. Canoo, Mullen Automotive, Faraday Future, Lordstown Motors and Nikola Corporation are still in business, but with cratering share prices.

The only big winner in this segment is Tesla. According to the Motley Fool, it’s the only company in the world that’s made more than a million fully electric units. If you count hybrids, China’s BYD takes the lead, and only Volkswagen, GM, Stellantis and Hyundai have seats at the grownups’ table.

According to Money magazine, the average gas-powered car stays on the lot for two months, but the average EV stays there for three. Americans are just not in a rush to go electric. There are lots of reasons for that, but the main ones – aside from sticker price – relate to charging. The infrastructure just isn’t in place, and you can’t rely on finding a convenient charging station on an intercity road trip. And even if you did, charging at a public station can be exorbitantly expensive compared to plugging it in at home. This has given rise to the term “range anxiety”.

But to return briefly to autonomous vehicles, what makes them go is AI. And that’s another technology that is still in its early days. The concept goes back to at least the 1950s, but commercialization is still very new.

Whether we’re discussing advanced driver assistance systems, large language modules or some other AI use case, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers has a few words of warning:

- Human errors in operation get replaced by human errors in coding. Whether it’s a human or a machine, the “driver” is probably the last link in a series of factors that contribute to the crash. “Software code is incredibly error-prone, and the problem only grows as the systems become more complex,” Missy Cummings wrote for the IEEE’s journal. “While a language model may give you nonsense, a self-driving car can kill you.”

- AI failure modes are hard to predict. You can’t model everything, nor can you know all the real-world effects a model might have. Cummings pointed to self-driving taxis’ tendency to hit the brakes for no apparent reason.

- Probabilistic estimates do not approximate judgment under uncertainty. In other words, machines have no real knowledge or judgment, only data, so they will still make bad decisions.

- Maintaining AI is just as important as creating AI. The environment changes, so training data must be updated. You can’t expect a machine to just intuit what an electric bike or an articulated bus – one of those new, double-length buses that bend in the middle – is if it hasn’t been trained for them.

- AI has system-level implications that can’t be ignored. Self-driving vehicles stop dead rather than face uncertainty, so they’re only as good as the local 5G. One time, there was an outage in downtown San Francisco and 20 Cruises froze on the spot, causing a traffic jam.

The takeaway is this: AI isn’t coming for everyone’s job anytime soon.

At the close

And that’s unfortunate in one regard: autonomous trucks would be great. There’s been a shortage of long-haul truckers for decades and it’s just getting worse. So many supply chain issues could be resolved by anything approaching full automation. It’s a dangerous, tedious and demanding job, and any enhancements would be welcome. It’s good to know that not only Tesla and Waymo are working on it, but also Daimler, Volvo and several other entrants. There has been some success throughout the southwest U.S. with most promising technique being “platooning,” in which an automated fleet follows a lead truck with a human driver.

Still, it’s safe to say the future isn’t arriving ahead of schedule. There is money to be made if you’re willing to be patient, but it could take years before the true value of any of these technologies are unlocked.

And let’s not forget one of the main reasons the Nasdaq was up 43% in 2023: It was rebounding from being down 33% in 2022.

For every winner in new technology fields, there’s bound to be a dozen losers. You might want to consult an experienced financial professional to help you direct your investments.