Market Overview

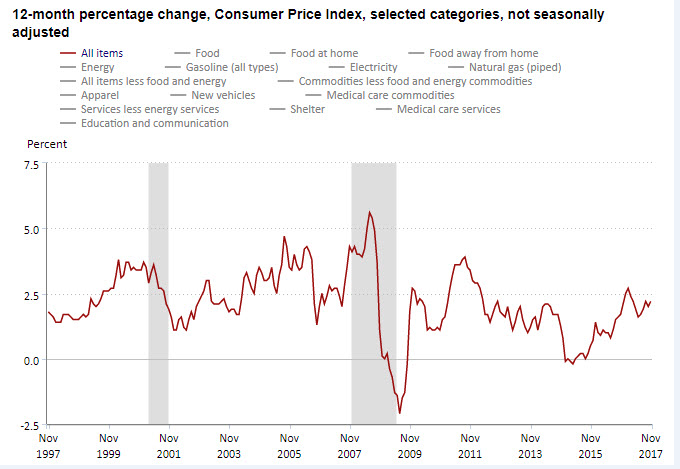

The U.S. economy stands in an enviable position today. People old enough to remember “stagflation” know that the current environment is the exact opposite: a growing economy with easily available credit that somehow has yet to show signs of steepening inflation. Gross domestic product is projected to grow 2.5% in 2018 – toward the high end of what is considered sustainable. One question worth asking is: How did we get here? A more important one, though, persists: How much longer can this be sustained? The answers might have less to do with numbers and more to do with the individuals charged with achieving them.

This past year was as eventful as any the U.S. markets have ever seen. What follows is as brief a summation of the year’s investment news as can be conveyed, considering how much there is to cover in this space.

By all accounts, 2017 was densely packed with news and not all of it good. New controversies, renewed rivalries, and heightened tensions both at home and abroad have made for a year of anxiety for many – and a holiday season of awkward family dinners for just about all. President Trump’s strained relations with congressional leaders of both parties, controversial appointments to key positions, and frequently outrageous Twitter stream have often fanned the flames.

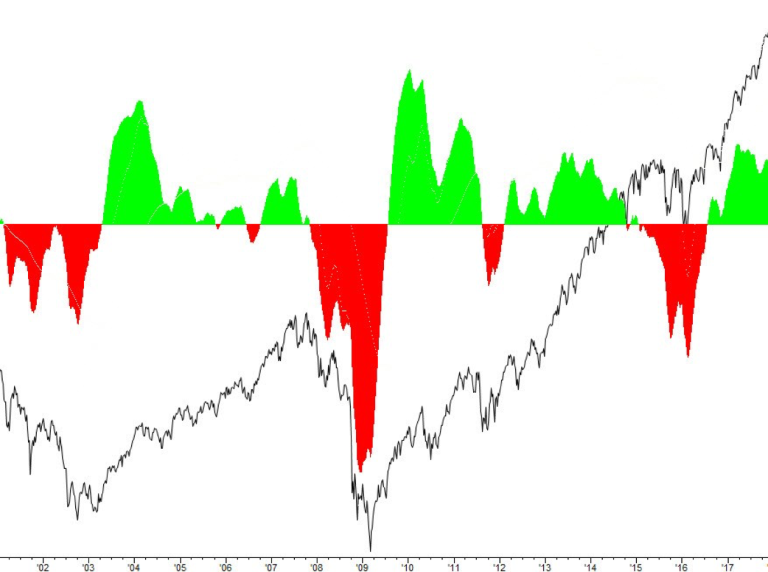

Still, the S&P 500 was up more than 21% for the year. The CBOE Volatility Index – the so-called “Wall Street fear gauge” better known by its symbol, VIX – has been grinding along near historic lows, suggesting that investors see no immediate end to the surge. Unemployment continues its downward trajectory, and many economists believe that it could soon reach its practical minimum.

President Trump’s first year in office, then, has been a genuine success as far as the markets are concerned. The financial industry clearly sees these times through a different lens than much of the rest of the U.S. population.

That is partially due to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the first major rewrite of fiscal policy since 1986. But tax reform is at most a quarter of the story. The Dow was already up around 20% for the year by the time the bill was under serious consideration. Further, the Republican majority in the 115th Congress had not yet reeled in a major legislative victory, so Wall Street was unlikely to price in a tax break until it could believe its passage was assured. (See the related article on what the tax reform law means for the typical USPFA member.)

Rather, a larger part of the reason why markets looked beyond the late-night monologues is that President Trump’s appointments to posts related directly to the financial industry have been solid picks – technologically sophisticated professionals whose bona fides as finance practitioners are beyond reproach by all but the most strident partisans.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin offers a resume that stretches from Wall Street to Hollywood, with expertise in information systems as well as media and mortgages, and served as architect for the tax reform law. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, a longtime Democrat and onetime Clinton appointee, is one of the nation’s premiere turnaround specialists. National Economic Council Director Gary Cohn is known to be a champion of American smokestack industries and to have more nuanced views than his boss on international trade. Top economic advisor Kevin Hassett is the kind of classic monetarist who connects well with fiscal conservatives and takes some rough edges off the administration’s stringent immigration policies. Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Jay Clayton might seem an odd choice – regulators generally favor regulation – but the high-powered mergers-and-acquisition attorney is clearly qualified, and he intimately understands the industry he will oversee.

Ultimately, though, the President’s highest marks are reserved for his appointments to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

Chairman-designee Jay Powell is only the most notable in a string of good picks. The seated Fed governor has as much bipartisan appeal as can be found in Washington today. Barack Obama originally named him to the Fed despite his identification with the Republican Party. In younger days, he served as a Treasury undersecretary for George H.W. Bush. Although he shares the prevailing skepticism of the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial regulatory overhaul, he recognizes that some degree of oversight facilitates capital markets and, thus, strengthens the economy at large.

As much as the President makes headlines by walking away from trade deals, it is instructive how many of his appointees to prominent posts hold a global perspective on commerce. Powell figures conspicuously among them. Although he shares the administration’s stated concerns for those whom open markets leave behind, Powell is very much an advocate for open markets.

And yet he is not standard-issue Fed material. Central bankers tend to be tweedy, academic types in the Volcker-Greenspan-Bernanke mode and, despite Powell’s terms in public service, he is very much a practitioner. He worked first in M&A, then private equity.

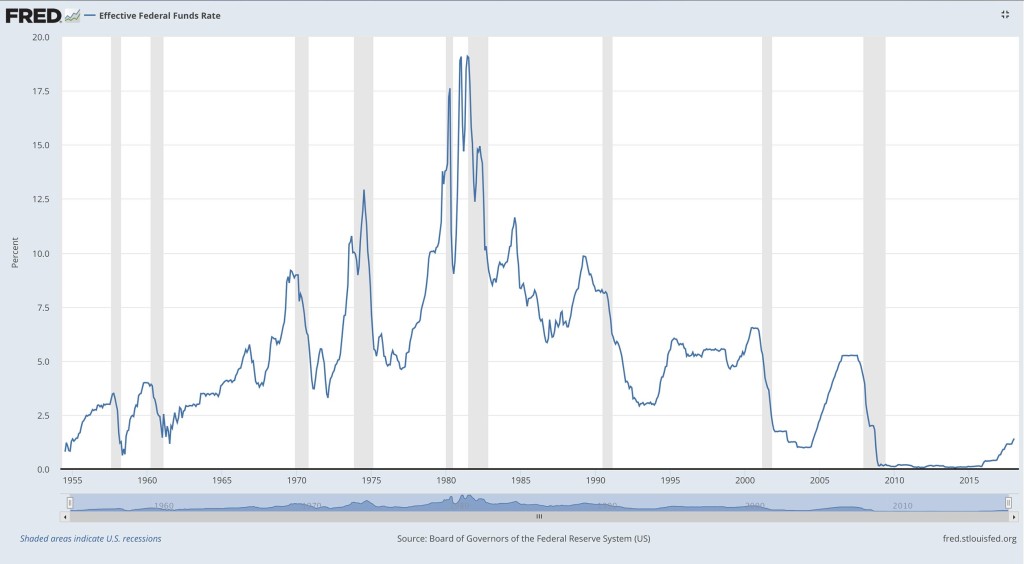

His predecessor, Janet Yellen, was something of a transitional figure. An unemployment fighter by inclination, she set the stage for a more inflation-proofing Fed, raising the target Fed Funds rate over the past two years from the minimal 0.25% to the current – still low – 1.5%.

Yellen has chosen to retire when Powell succeeds to the chair this month. Mr. Trump has not yet named a successor but, then again, he has some catching up to do first.

Apart from elevating Powell, the President has already nominated two Fed governors, one of whom has already been seated. Still, three vacant seats on the board remain -- and that is not even counting Yellen’s. Altogether, Mr. Trump is in position to name six out of the seven board members.

It will be his Fed long after he leaves office and, so far, it appears he is providing a sound legacy at the central bank.

Mr. Trump’s first pick was Randal K. Quarles. What is most intriguing about him as a choice for a Fed board seat is the way he represents a balance between seasoned insider and incisive outsider. Like Powell, Quarles was a Bush Treasury official – albeit under both Presidents Bush. Bush 41 assigned him a role containing the savings-and-loan crisis, and he served as the department’s resident firefighter for Bush 43, tackling crises as divergent as Argentine debt default, preventing implosion at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and the U.S. response to Chinese currency controls.

But also like Powell, Quarles is not an economist or central banker by trade. He too comes from the private sector, specializing first in M&A for the financial industry, then moving into private equity, then wealth management.

Quarles is the governor in charge of bank regulation – a role that had gone unfilled since it was created by Dodd-Frank. This is undoubtedly the role he would have selected for himself. His was the voice in Bush 43’s administration calling for more regulation of financial institutions; he left in 2006, and history records what happened next.

Mr. Trump also nominated Marvin Goodfriend, yet to be confirmed by the Senate, whose main focus is inflation fighting. That makes perfect sense in the context of a Fed presiding over an economy verging on a labor shortage.

What makes Goodfriend a potentially controversial selection – and perhaps an inspired one – is that he does not seem to think the Fed should matter as much as it currently does. The Reagan Revolution veteran is a strict empiricist who believes that much of the art of central banking can be reduced to a science. His academic work suggests a mathematical, rules-based determination of monetary policy would take the guesswork out of what actions the Fed would take.

Still, Mr. Trump has three more appointments to make. Speculation of whom those might be have turned even the most august financial news outlets into gossip columns. The only name worth mentioning here is John Taylor, who is widely believed to have been runner-up to Powell for the chairmanship. The job of vice chair, currently open, is likely his if he is willing to accept the No. 2 position.

Taylor is simply one of the most renowned American economists. He is best known for his staggered-contracts model of setting wage and price expectations, for which many believe he is overdue for a Nobel Prize. Like Goodfriend, he is an academic – currently at Stanford – and, like Quarles, he served in both Bush administrations and is not a strict monetarist. He is also an empiricist who formalized a mathematical rule to link a central bank’s targeted interest rate to economic data in order to tamp down inflation.

Assuming Taylor is willing to serve, the President could nominate equally respected, sober-minded economists and financiers. Alternately, he could bow to his populist base and name economic isolationists or anti-Fed libertarians, knowing that they would be outnumbered and unlikely to influence these technocrats with more moderate viewpoints.

Given that expertise and balance among its Board of Governors, the Fed should continue to raise interest rates to keep inflation at bay. Taylor’s work suggests he might favor increasing the target Fed Funds rate by a percent or more at a time, but it is more likely the central bank will inch along a quarter percent at a time as long as price increases remain tame. Providing this remains the case, equity markets should continue their rise.

Ultimately, though, the continuation of easy credit and stock market growth are not a Washington story. They are a factor of corporate earnings, which are in turn a factor of consumer demand.

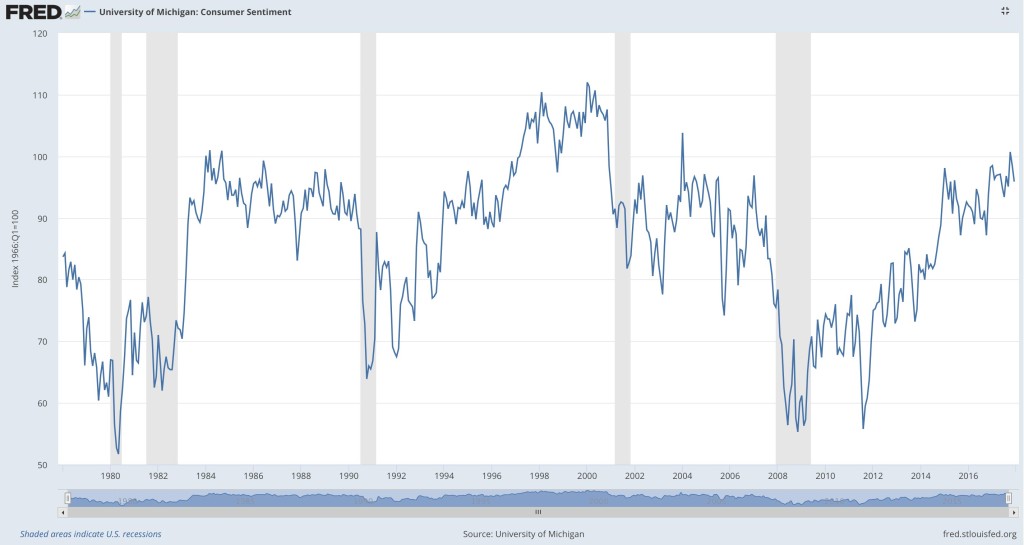

Household income has been rising for five years straight. Consumer confidence has not kept pace but is still heading in a positive direction. Taken together, this bodes well for demand.

As consumer demand raises revenues and technological innovation continues to lower costs, corporate earnings are likely to keep growing.

This cannot continue forever, of course, but indicators suggest continued growth through 2018. The economy is cyclical, though, and a recession will happen eventually. The only cloud on the horizon is the flattening yield curve – that investors are not being rewarded greatly for buying longer-term Treasury bonds as opposed to medium-term Treasury bills. The Fed might not be able to help with this and could conceivably exacerbate this situation as it works to unwind trillions of dollars of Treasury instruments on its balance sheet. At the point where the curve inverts and T-bonds actually pay less interest than T-bills, a recession is virtually inevitable.

Still, unless there is some catastrophe that takes the world by surprise, 2018 should be another good year, although 20% stock market growth is a lot to ask two years in a row.