Market Overview

This month’s models are now available.

Property taxes, and what to do about them

You’re probably among the 60 percent of U.S. homeowners whose property is overvalued for tax purposes, at least according to one study. According to another, you’re also probably one of the 98% who hasn’t done anything to address this injustice.

But there’s plenty you can and should do to trim your property tax bill because no municipality is going to voluntarily start the process for you. Not only would it be reducing its own revenue, it would also – assuming you’re not the only one reacting to being overcharged – lower the average reported home value in the community, taking away some of its bragging rights.

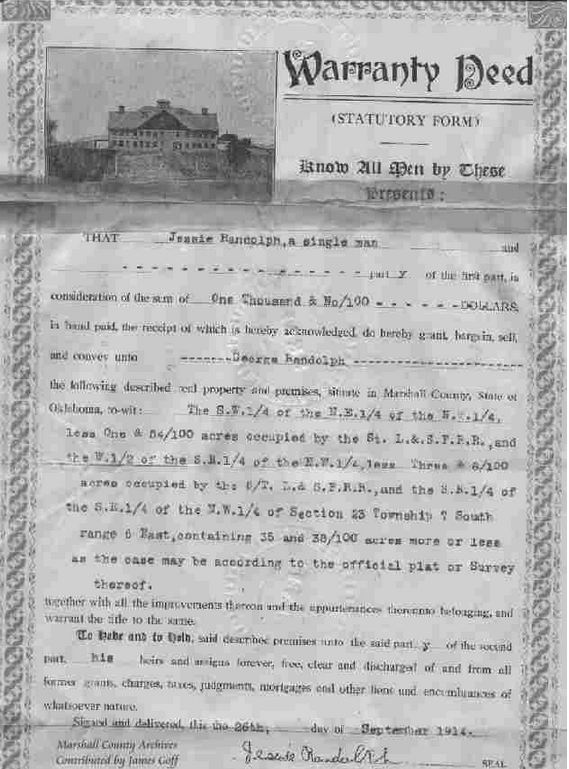

An early 20th century Virginia man realized the American dream of home ownership. Credit: MrWilliamsburg.com

Civic pride is fine, of course, but you should control how much it’s worth to you. Here’s how to minimize that direct tax on the American dream.

Bringing down the tax bill

Find out what your assessed value is and how it was determined. Location is, of course, the key determinant of what your home is worth. Square footage, zoning restrictions and improvements to your property are also important factors. City Hall might not make it easy for you to find, but your home’s assessed value is public information that must be disclosed on request. It’s on a document called a property card, and you have every right to stop by your local tax appraiser’s office or website and receive a copy of it. While you’re there, get copies of your neighbors’. If their values are far lower than yours, then you have an excellent case. If their valuations are comparable to yours, then you have natural allies in your case that the entire neighborhood could be facing an overcharge.

Challenge your assessment. There’s no shortage of information about what your home’s market value is. Realtor.com, Zillow and any number of other online resources are free for you to use. Private assessors are available locally – you can do a Web search or you can ask the broker who sold you your home for a referral. Be sure you know when the deadline for filing a challenge but, even if you miss it, persistence could pay off. There’s always next year.

Take advantage of incentives. Could adding solar panels give you a property tax credit? Could being a veteran or senior citizen give you an exemption? Many states, especially in the South and West, offer a so-called “homestead” exemption which shields homeowners from having to pay taxes on a portion of the assessed value. Check with your state and local tax authorities.

Or maybe not. Be careful what you wish for, because you might just get it. Is your property 100% up-to-code? Did you ever put up a shed or even an exterior electrical outlet without a building permit? Make sure you’re not inviting scrutiny that could make you wish you hadn’t made a fuss.

Be kind to the assessors. They’re just doing their jobs, just like the retail clerk at the mall. And, just like that 19-year-old slouching against the discount rack, the assessor is in a position to do far more for someone who’s being nice than to someone who’s being sort of a jerk.

Don’t be the prettiest house on the block. This piece of advice – and the next one as well – are the exact opposite of what your real estate brokers will tell you. That’s because their job is to maximize your value and what you’re trying to do for tax purposes is minimize it. So let the Joneses win the war of the rose bushes. Let them have the fuller lawn and more distinctive shutters. Saving on landscapers and painters adds to your saving from lower taxes.

Think twice before improving your property. If you’re going to add a screened-in porch or widen your garage or construct any other permanent structure, that’s going to increase your property value and thus your assessment. An addition that only costs $10,000 one-time to build could end up costing you that in incremental taxes over the course of just a few years. So live without it for as long as you can – then bolt it on as soon as you start thinking about selling.

It could be worse

Whatever you pay for property taxes, it might be a comfort to consider that, under policies derived from another set of economic assumptions, you’d be paying a whole lot more.

Before the current tax reform bill was taken up, much ink had been spilled concerning a “flat tax.” You might have first come across it as the cornerstone of Steve Forbes’s 1996 presidential campaign. Since then, it has been a frequently cited goal of many in politics – mostly conservatives, but even liberal California Gov. Jerry Brown flirted with the idea at one point.

That flat tax applies to incomes, but an earlier version did not. American economist Henry George proposed that there be only one tax to cover all government expenditures for every purpose at every level. It wouldn’t be a tax on income, nor would it be a tax on sales. It would be a tax on wealth which, in 1879, was almost synonymous with real estate property.

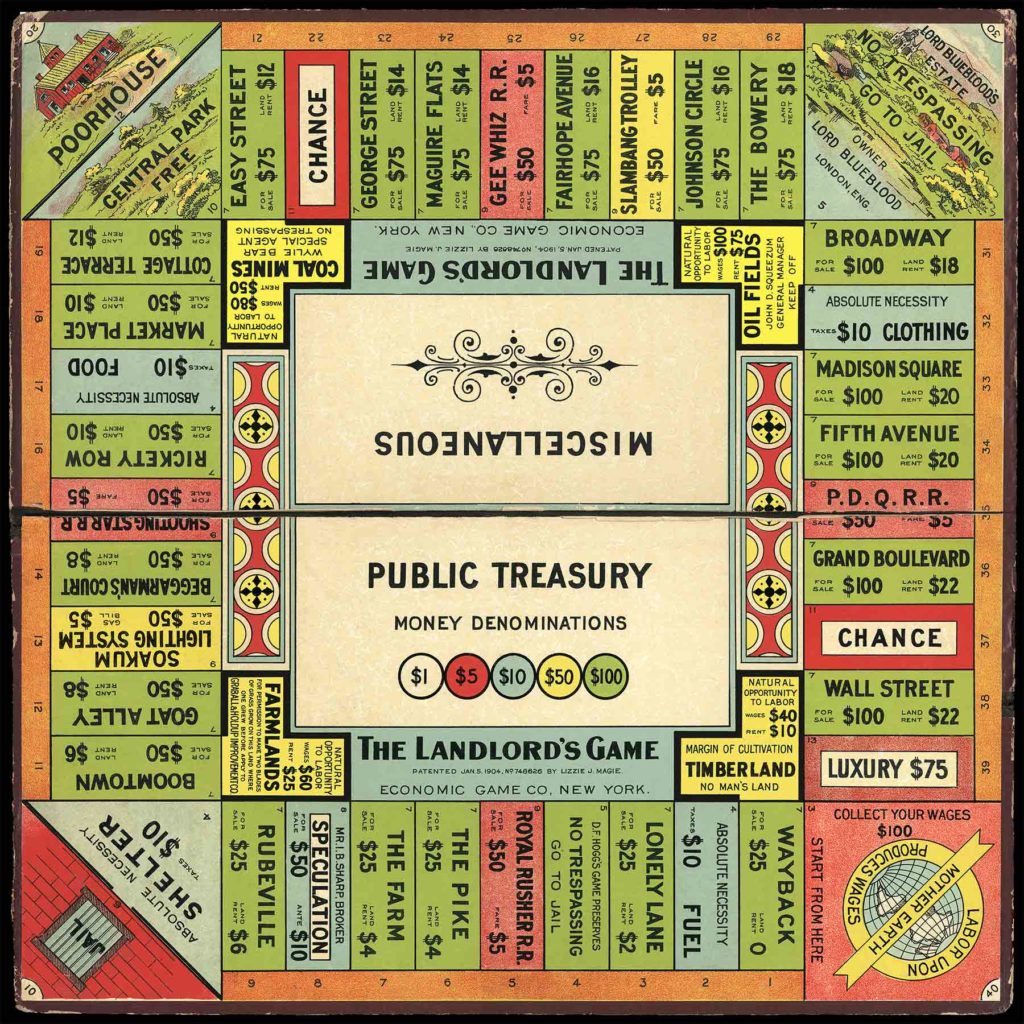

The Landlord’s Game, a 1906 precursor to Monopoly, was developed to teach about Georgist economic theory. Credit: TheLandlordsGame.com

That might sound Marxist to us but it didn’t to Marx, who considered a tax on private property to be a backhanded endorsement of private property. Still, thinkers from Aldous Huxley to William F. Buckley Jr. have considered themselves Georgists, as have world leaders from Sun Yat-Sen to Winston Churchill. No less a supply-sider as Milton Friedman described a levy against property as the "least bad tax".

Once the current round of tax reform becomes the status quo, it’s inevitable that someone will be displeased enough with it to propose another round. When that happens, someone might ask you: Would you accept an annual tax on your property if it meant never paying another penny on your purchases and never filling out another 1040 form?

If you don’t have a ready answer, you might want to put the question to a professional financial advisor.