Market Overview

This month's models have been posted. There are CHANGES in ALL MODELS (highlighted in yellow).

The dollar is strong. No, really.

It’s entirely fair to say that the U.S. dollar doesn’t buy as much as it did a year ago. It’s also true that, although the entire world is experiencing inflation right now, American consumer prices have surged a little higher than those of most other advanced economies.

And yet, the news is not all bad when it comes to the value of the greenback.

If the price of gas is going up, why isn’t the price of gold? Credit: Stevebidmead

You usually don’t see gas prices and car prices rising at the same time – you’d think those big numbers outside your Exxon station would dissuade people from spending too much at the Chevy lot across the street. But these aren’t ordinary times. Two years of going stir-crazy have made a lot of people willing to pay top dollar for cars and trucks – new or used, or even just the parts. Obstacles stemming from the pandemic’s rapid industrial shutdown and slow restart are affecting supply just as demand is peaking – a recipe for inflation, at least in the automotive space.

Other supply chains issues – now more closely related to the war in Ukraine than to the one against the coronavirus – have disrupted the delivery of both oil and agricultural goods, leading to higher prices for these commodities. And yet economists are quick to point out that energy and food prices are “non-core.” They don’t mean that gasoline and meat aren’t important, just that their prices are more volatile than others’, there’s little any government or firm can do about it, and we might as well set them aside when making policy choices. The best you can hope for is that the markets will straighten prices out eventually.

Exchange study

And make no mistake: Inflation is real, even among such core components as apparel and housing. Overall, the price of everything excluding food and energy went up more than 6% over the past year. It’s strange days indeed when the costs of medical services and prescriptions are among the most stable.

Despite all this tangible inflation, though, we’re left to wonder:

- If the dollar is declining, why is the dollar-denominated price of gold so stable?

- If the dollar is declining, why does it buy so much more in terms of pounds, euros or yen?

- If the dollar is declining, why are the prices of so many consumer expenditures not soaring while others are?

While world currency markets stabilized in May, it’s incredible how much stronger the dollar got against other reserve currencies from January through April.

While gold rose 5.4% -- far below the rate of U.S. consumer prices – the dollar gained almost 7% against both the pound and the euro. Meantime, the yen had lost more than 11% of its value in dollar terms, sinking to a 20-year low.

This means we might not be able to afford such top-shelf domestic bourbons as Old Forester anymore, but our dollars will buy more Lagavulin scotch, the Yamazaki Japanese whiskey or – while we’re splurging – Puni Aura, the first high-end malt out of Italy. More broadly, we’re in a position to import goods from overseas more cheaply than we can make it here, so that will tend to keep a lid on inflation.

What makes a dollar worth a dollar

The comparative value of currencies has much more to do with what the different countries’ central banks are doing strategically than with where their consumer price indices stand this month.

The dollar, euro, pound and yen are all considered reserve currencies. That means they’re all issued by the monetary authorities of sovereign nations with a long history of always paying their bills on time. If you’re a government or firm with major treasury operations and you want to lend money issued by any of central banks responsible for reserve currencies, you’ll have to settle for a low interest rate because there’s virtually no risk. If you want a high return on taking out a loan in a foreign currency, try Argentina or Venezuela.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Federal Reserve moved ahead of its peers around the post-industrial world and aggressively raised interest rates. So as the Fed funds rate hit 1% -- not that high historically, by the way – the U.K.’s equivalent LIBOR rate was only 0.84%. In other words, you could make 1% if you extended risk-free overnight loans in New York every night for a year, or 0.84% in London. When you’re dealing with billions of dollars, yes, it makes a difference.

Policy prescriptions

None of this is going to last. Currency markets have gotten boring again, and let’s hope they stay that way. The Bank of England has already moved to match the Fed’s actions, as has the European Central Bank. The Bank of Japan has always marched to a different drummer, which is why it’s not experiencing any unusual inflation now in contrast with virtually all other developed economies.

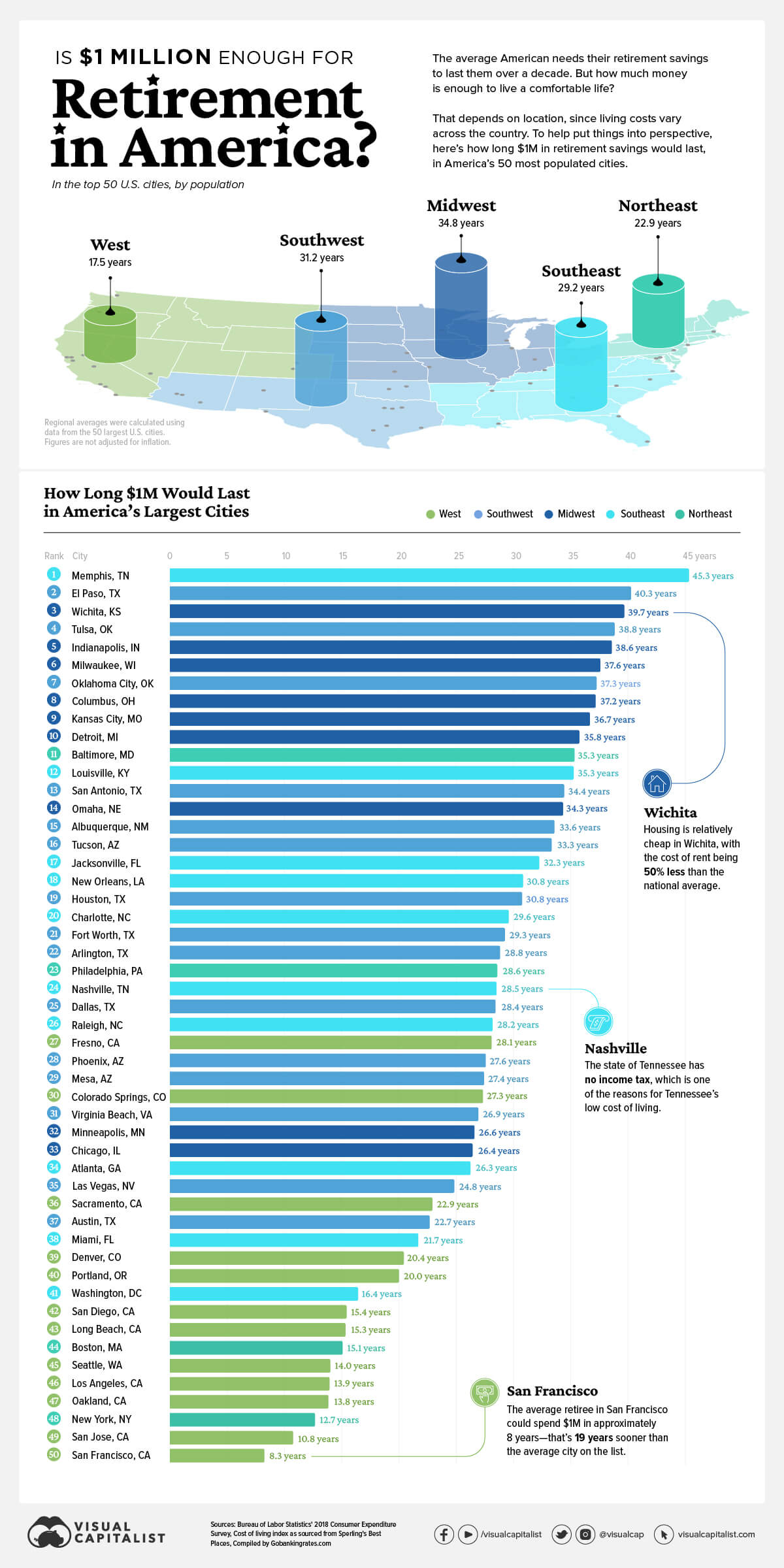

But it is a big world out there, and a move by the central bank in Tokyo could send a ripple through markets and affect the cost of finished goods in Wichita, KS. Moves by the People’s Bank of China could swamp those markets. You might want to hear what your trusted financial advisor has to say on the subject.