Market Overview

Strategizing for the late innings

With baseball post-season just a wistful memory away, we wanted to make the analogy of how a manager of a tight game might change strategies, bringing in a new pitcher to protect a narrow lead or putting in unheralded bench players to use “small ball” tactics to manufacture a much-needed run.

But then Steve Pearce swatted a two-run homer in the first inning of the decisive Game 5, and Boston went on with a no-looking-back 5-1 victory over the Los Angeles Dodgers.

So what does that mean to us – aside from another reason to hate the Red Sox?

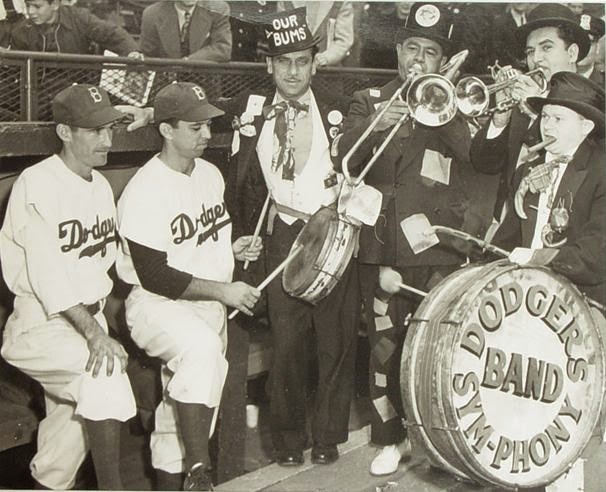

Somewhere out in the Great Beyond, these Dodger fans share their descendants’ 2018 heartbreak. Credit: North Brooklyn History Blog (historicgreenpoint.blogspot.com)

Even the mighty Casey struck out

The analogy still holds. As you get closer to retirement, you’d be well advised to fine-tune your degree of aggressiveness as an investor. In truth, it’s a great idea to review your appetite for risk and how that translates to portfolio mix regularly, probably more so when we’re later in the cycle and the environment feels riskier. In a very real way, rocky markets help us better understand who we are as investors. We’re either comfortable or we are not. Listen to your inner voice. How do you feel right now? A great way to do this, in our experience, is to stop thinking about how much money you have and start speculating how much time you have. Once you’ve adjusted your thinking along those lines, then the following questions help you better understand who you are as an investor: “If all my long-term investments start losing value, how do I respond? Do I know my threshold for negative market movements? How is my short-term money positioned in terms of risk? If everything worsens in the coming months, do I have plan for covering my expenses?”

It quickly becomes apparent, then, how these questions change over time – not just in the actual number of months or years, but also in how strongly you respond to these questions. While you’re working and making money, you can shrug off a paper loss, even a sizable one, knowing that you still have years of productivity ahead of you to make up the shortfall. As you near retirement, not so much. With home and educational expenses winding down, you might actually be able to live comfortably much longer on your accrued cash than when you were in your most energetic years, but now it becomes imperative that you be able to.

It’s a team sport

When it comes to your retirement strategy, many people take on a player-manager role. Time for a history lesson.

The player-manager role was already a tradition in baseball when Connie Mack became one in 1894. Such legends as Leo Durocher, Mel Ott and Frank Robinson are among the dozens who share that distinction. So does Pete Rose but, regardless of whether he deserves a place in the Hall of Fame, he doesn’t deserve a place in any investment newsletter.

But even the most vibrant player-managers ultimately have to rely on their teammates. When picking investment vehicles, as on the field of play, a lot is left to chance. The best you can do is play the percentages and, through intellectually rigorous judgment, play those odds just a little bit better than the anyone else in the division.

For that, it’s important to check your gut feelings against the wisdom of your bench coach. Dalbar, a consultancy focused on the financial community, has made a name for itself with its signature Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior. Although the QAIB is updated annually, its results are pretty much constant: A lot of investor activity is utterly irrational. According to Dalbar, “psychological factors” account for half of all investor shortfalls.

This isn’t news. An entire academic discipline, behavioral economics, arose over the past three decades to explain why people are so short-sighted with their money. But Dalbar identifies nine specific quirks of human emotion that lead to much of the financial pain.

Primary among them is what’s called “herding,” which is exactly what it sounds like. If you’re just following the market, you shouldn’t be surprised if you find yourself buying high and selling low. This is followed by “loss aversion.” Many investors are so afraid of taking a loss on any one play that they’ll sell into a bear market. But even if they hold onto that asset until after the panic has subsided, they’re then more likely to keep it in their account and wait for it to “turn around.” They can handle the paper loss, perhaps, but they’ll be very resistant to actually taking less cash for it than they paid. These are the greatest challenges to the player-manager role in personal finance.

Emotional decision making is the same as an unforced error. And while unforced errors cannot be completely eradicated in the game of money management, they can be significantly reduced with good coaching from a team of professionals. So here’s the takeaway: Gather solid data, and rely on it. Modern baseball has moved on from the player-manager. We live in the age of sabermetrics, the statistical analysis made famous by the Michael Lewis book and Brad Pitt film Moneyball, and there isn’t a manager anywhere in the big leagues anymore who makes a move because “I got a hunch.”

Over time the game gets more serious. You are accumulating more wealth. You are nearing retirement. You are doing all you can to confidently prepare for a long and happy life. It’s the World Series of personal finance, and you’re in the playoffs, Champ! It’s not just about decisions but the decision-making process. Not everyone can handle the pressure on their own, and that’s where good coaching comes into play.