Market Overview

This month’s models are now available.

Commodities: Hard assets for hard times

In normal times, investment advisors often tell you to diversify your portfolio into three broad categories: equities, fixed income and cash equivalents. What proportion you put in which bucket is a judgment call, as is the frequency with which you rebalance your portfolio. And of course, the art lies in picking the right vehicles within those categories.

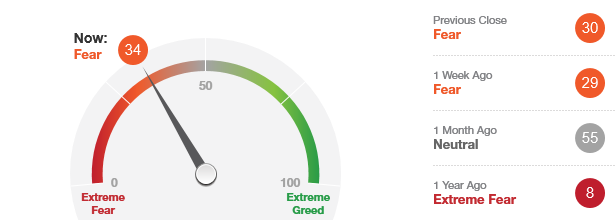

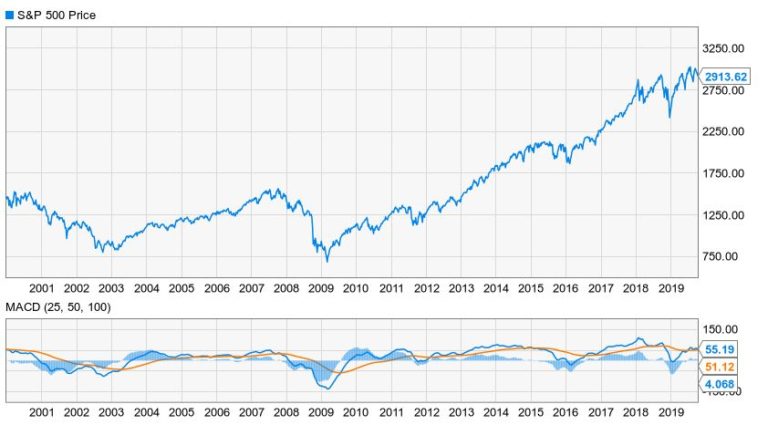

But these are hardly normal times. Political and economic turmoil swirl around not only in the United States, but also the United Kingdom and the European Union. Somehow, we’re managing to sustain the longest economic expansion in history but, as we discussed here previously, that won’t last forever.

So, what’s your plan for your post-Great Expansion nest egg? What if the stock market turns bearish, the yield curve continues to penalize long-term savings and the Federal Reserve continues to increase the money supply come what may? In other words, what if equities, fixed income and cash were all to lose value at the same time? You might want to ask a financial professional now about whether it’s a good time to put some of your money into such alternatives as commodities.

The oil trader next door

A commodity is basically anything of tangible value that is not specialized in any way. That is, one barrel of oil is much like any other, as is any bushel of corn or any ounce of gold, presuming they’ve all been standardized for quality assurance.

Chicago Board of Trade corn pit, 1993. It’s all on phone apps now.

This is different from equities in that no two companies issuing stocks are exactly the same. They all have different technologies, physical plants, marketing strategies, costs of capital, labor contracts and management talent.

Commodities fall into five broad categories:

- Precious metals, such as gold and platinum;

- Industrial metals, such as iron and steel;

- Energy, such as oil and natural gas;

- Livestock, such as pork bellies and live cattle; and

- Agricultural products, such as sugar or cotton.

You’ll notice that there’s one unspecialized asset of tangible value is missing: money. Currency markets are their own thing, and we’ll take a look at them in a future article. (Cryptocurrency, which is an entirely new asset class, could also be viewed as a commodity. While it seems to have matured to the point where there’s a semblance of stability in the crypto market, it’s probably still too volatile to consider as part of a retirement portfolio.)

According to the Futures Industry Association, the most widely traded commodities are:

- Brent crude oil

- Steel

- West Texas intermediate crude oil

- Soybeans

- Iron

- Corn

- Gold

- Copper

- Aluminum

- Silver

IG Group offers an excellent primer on these.

Entry points

It’s important to understand that you’re not actually trading commodities when you’re trading commodities. You’re trading derivative securities predicated on the exchange of the goods. Yes, somebody actually has gold and somebody else is going to end up with it. In real life, this usually means that the ownership of the bars is transferred but the metal itself stays where it is or just gets forklifted over to another pile in the same vault. Somebody else has been raising hogs and somebody else is going to turn them into kielbasa, but you don’t need to get your shoes dirty.

Trading in these derivatives can all be executed through phone apps or with the click of a mouse. It is generally done through futures contracts. These are standardized agreements traded on an organized exchange to buy or sell assets at a fixed price but to be delivered and paid for later.

You can also buy options on these futures contracts. These give you the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a futures contract at a given “strike” price on or before the option’s expiration date.

Whether you should trade in futures, options or both is a complicated calculation, and many advisors recommend finding a more intuitive path for their clients whose day jobs keep them busy enough.

Fortunately, there’s an alternative: exchange-traded funds. You probably already have ETFs in your portfolio, matching the performance of the S&P 500 or some specific component of the index, or perhaps matching fixed-income or non-U.S. stock benchmarks. It should come as no surprise that there are ETFs for which commodities futures are the underlying assets. They generally track the S&P GSCI Total Return Index.

One last class of vehicle to mention here is contracts for difference. CFDs are arrangements – usually through a broker rather than an exchange – in which the difference between the opening and closing trade prices for a futures contract is settled in cash. They originated in 2001 as a tax dodge in the United Kingdom and quickly spread around the globe. While CFDs are used internationally by experienced traders, they have never been legal in the United States. The Securities and Exchange Commission considers them the next generation of “bucket shops,” which were essentially bookies masquerading as brokerages that flourished from roughly 1870 through 1920.

Words of caution

That CFDs are banned in America should tell you something of the inherent risk of commodities trading, but not everything.

The fact is, you can really lose a lot of money in commodities. Let’s assume that you’ve decided to eschew the futures market and go with what appears to be the safer ETF route. You should know that even this isn’t as secure as it appears. These funds are often structured as trusts rather than as mutual funds. Operationally, that makes little difference, but it means that these vehicles aren’t subject to the same regulatory requirements as other ETFs. It would be best to discuss the potential downside with a qualified financial professional.

But you don’t need expert advice to know that the commodities market and the stock market tend to move in opposite directions. If you’re betting big on commodities, you’re in essence betting big against stocks. The last time commodities peaked was in the early days of the Great Recession, and it was a very short-lived rally. If you got in and out at the optimal times, then you made a lot of money. But if you bought at the peak in 2008 and you’re still holding that position today, then you’ve lost more than two-thirds of your stake.

According to a Yale University study, returns on investment in commodities have diluted as more retail investors have gotten into the game.

“Commodity futures offer a fascinating case study of what happens when any investment idea becomes too popular,” according to a Kiplinger article summarizing the findings.

Just something to think about. Even with this caveat, though, now might be a very good moment to get into commodities, at least as a hedge. Commodities are undervalued right now compared with other asset classes and they’re becoming hard to ignore. How much of your portfolio you should allocate to that position is your decision, best made with input from an experienced advisor.

Weston Pollock is a Managing Partner at Smith Anglin Financial, and leads the firm’s marketing and business development. He regularly meets with prospective clients, counsels existing clients, participates in investment portfolio analysis and develops materials for communicating with the firm’s clientele and target markets. He holds a BBA in Finance and Real Estate and numerous securities licenses and designations.

Weston Pollock is a Managing Partner at Smith Anglin Financial, and leads the firm’s marketing and business development. He regularly meets with prospective clients, counsels existing clients, participates in investment portfolio analysis and develops materials for communicating with the firm’s clientele and target markets. He holds a BBA in Finance and Real Estate and numerous securities licenses and designations.