Market Overview

This month’s models are now available.

High bond yields persist – should you stay in?

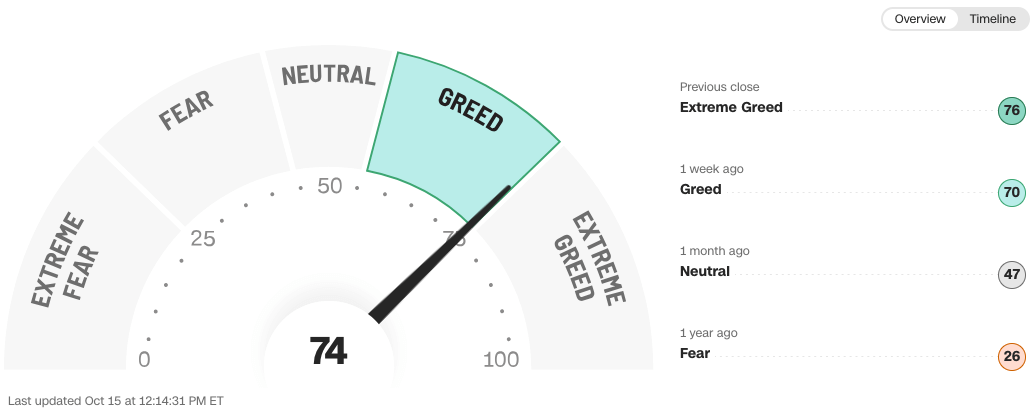

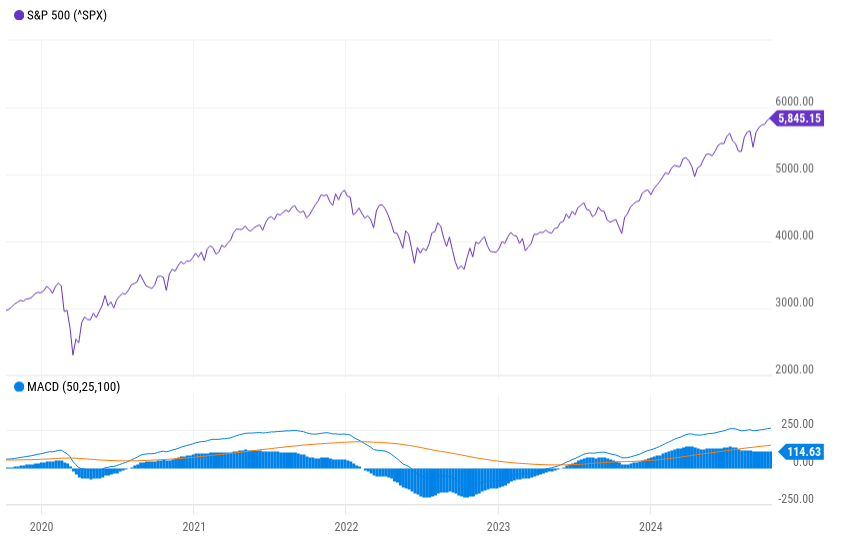

You probably noticed that, over the past two months, the S&P 500 index went up by somewhere around 12%. So, it’s probably a good time to rebalance. But which way? If you want to lock in your gains, then you might want to switch to fixed-income instruments. If, however, you want to take advantage of the momentum equities are experiencing right now, you might want to move some of your capital out of bonds and into stocks.

To Team Momentum we say, “Yes. Absolutely. Except …”

Bond yields are still high by historical measures, meaning they’re still providing solid returns to their holders. That’s despite the half-percentage point cut in target interest rates the Federal Reserve announced last month, and the further cut we all expect it to announce next month.

And what do we mean by “bond yields”? Which bonds? When we use the term, it’s usually shorthand for the yield of the 10-year Treasury security which, technically speaking, is a note rather than a bond. (Bonds are longer-term.) It also assumes constant maturity, which means that it’s not an official number but rather an estimate of the annual return of what the last person to buy a 10-year Treasury note on the secondary market should get.

The whole discussion ignores not only shorter and longer-term federally issued debt securities, but also all those bond and notes issued by municipal or corporate entities.

So, it’s probably time to cut loose some of your fixed-income holdings, but you shouldn’t be dumping the whole asset class all at once.

Still time to invest in Treasurys?

Whither bonds?

Just a year ago, we ran this headline here: “What not to do when both stocks and bonds falter”.

“Don’t panic,” was our advice at the time and we bet you’re glad you took it. We now have froth in both the equities and debt markets, and that’s a nice problem to have.

Still, 10-year Treasury yields seem to be defying gravity. The lower Fed funds rate means that banks can charge each other less interest, but that doesn’t affect Treasurys directly. Over time, lower bank rates work their way into lower bond yields, but it takes a while.

The shorter-term securities generally see movement first, and that’s the case this time around too. The bills – with maturities of a year or less – have already seen a drop. Just like they do in the stock market, fixed-income buyers act on the rumor, not the announcement, so the yield on the shortest-term bill dropped from 5.5% in late August to 4.9% shortly after the Fed’s announcement. You can expect it to fall further because it’s been as low as 3.4% post-pandemic and been darn near zero for most of this millennium.

Let’s take a quick look at the two-year note. That typically yields a couple ticks above zero, because you should be rewarded for committing capital for two years instead of one month. But that hasn’t been the case lately. While the current 3.7% is as high as it has been since the 2008 financial crash, it is still low when compared to the almost-cash-equivalent one-month bill.

Here's why that’s important: If you have certificates of deposit (CDs), your bank basically buys a bunch of short-term Treasurys, then pays you a rate that’s a little lower for the loan of your money. So, look carefully at the cardboard cutout at the front of the branch and don’t be surprised if the shorter-term CDs pay higher interest than the longer ones.

But the bonds and longer-term bills have a lot more to unpack. Like the shorter-term instruments, the 10-year has dropped from a peak of around 4.6% in April to around 3.7% at last reading. It’s likely to go lower, but it won’t be in a hurry. That’s because there is more to consider than today’s cost of capital. Long-term buyers concern themselves with expectations for not only interest rates but also exchange rates and inflation over the lifetime of the instrument. And of course there’s good old supply and demand; it takes time to unwind positions in longer-term instruments. Bond buyers eventually become bond sellers and, when that happens, they’ll probably be willing to shave a few points off just to unload them. The issuer – that’s the U.S. government – would then be able to save money by ratcheting down the yield for new instruments to the effective level of those trading in the secondary market.

Whither stocks?

Eventually, though, fixed-income supply and demand will balance out. The Treasury yield curve will – has already begun to – revert to its normal state of rewarding long-term commitment over short-term investment.

Then Treasury yields should trend lower. That, though, is an opportunity for other financial instruments to shine. Stocks and ETFs, sure. Commodities? Always helps to have a hand in. But what about other debt securities? This might be a golden hour for them. Whether you’re considering the higher yields of corporate paper – which is riskier than Treasuries, but varies widely by how much – or the additional tax shields of municipal bonds, you have a lot of alternatives to consider.

But let’s get back to stocks. And we should start by calling out one wildly erroneous misconception that has become so ingrained in the “common knowledge” of American finance that we have all blindly accepted it. That includes the editors of this newsletter. We see no malign intent behind this falsehood, but falsehood it is:

“Soft landings are very rare.”

We looked at the data. No, they happen almost as frequently as hard landings. To define our terms, “soft” means that an overactive economy slowed down to the point of sustainable growth. “Hard” means that the economy actually gotsmaller – it went into either a short contraction or a full-blown recession. If you continue to refine that definition, you’re left with what one economist tells us: that there’s been only a single soft landing in living memory: 1994-95. Others beg to differ.

According to BMO, an economics consultancy, the U.S. has seen four soft landings in the past 60 years. If you count the one we’re going through today – and we do – that’s five, compared with eight recessions. The Fed governors didn’t do such a great job at this in old-timey days but, over the past 30 years, they are batting .500.

This is important to us because, if we’re going to start picking stocks, it helps to know where we are in the economic cycle. We’re not in a contraction, even though a lot of very smart people thought that was exactly where we’d be today. Did we also skip the recovery phase because there’s nothing to recover from? If so, then we might want to look at such expansion-friendly sectors as Information Technology or Industrials. If not, then rebound stocks in the Consumer Discretionary or Financial sectors might be more appealing.

What you can do

But we never know where precisely we are in the economic cycle, just where we were – and that often requires a few months’ reflection.

And we on this side of your screen don’t know how well you have tax-shielded your portfolio, or when was the last time you rebalanced it.

Your trusted financial advisor might have some better insights about the cycle and certainly will have some ideas worth listening to when it comes to your own personal nest egg.