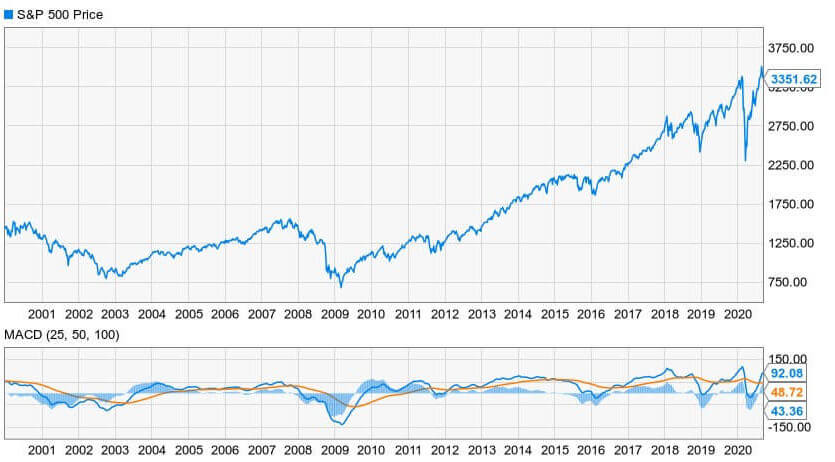

Market Overview

This month's models are posted. There are no changes in any of the models. The rest of the newsletter will be published by mid month.

Betting your dollar bottoms

In this space about a year ago, we discussed investing in commodities.

“So, what’s your plan for your post-Great Expansion nest egg?” we asked you, referring to the decade-long period of economic growth, which has since succumbed to the virus. “What if the stock market turns bearish, the yield curve continues to penalize long-term savings and the Federal Reserve continues to increase the money supply come what may? In other words, what if equities, fixed income and cash were all to lose value at the same time?”

Less than a year later, we’re past the Great Expansion. The stock market, despite its V-shaped recovery, continues to send bearish signals. Bond yields continued to flirt with inversion until the Fed announced recently that it would be willing to tolerate higher inflation down the road. However, that may create a new problem: What if that tolerance for inflation causes the value of the dollar to plummet?

The dangers of shrinking too far were well known since at least 1957. Credit: Universal Pictures

It’s already happening

The dollar is already losing ground against other world currencies, according to pairs generated by Yahoo Finance. Since March 20, the euro has gained almost 11% against the greenback. The British pound has gained more than 16% in the same span – and that’s after giving back a chunk in early September. Even the Japanese yen, which has been relatively stable against the dollar through all of this, is up around 4% over the past half year.

You could argue that the start date of March 20 represents a trough and, for the prior week, these currencies were all tanking against the U.S. currency on the (mistaken as it turned out) assumption America would be better insulated against the novel coronavirus than other developed economies. If such were the case, perhaps the sharp growth of non-US currencies is simply a rebound, and the foreign exchange rates are just returning to equilibrium. But the year-to-date comparisons suggest that the erosion of the dollar’s value abroad was already underway.

The New Zealand dollar, for example, is up more than 18% against the dollar year-to-date, and the Australian dollar is up more than 28% over the same span. Our neighbors’ currencies – the Mexican peso and Canadian dollar – are up over 8% and 10% respectively versus the greenback. Those two nations, by the way, are ranked No. 1 and No. 2 among U.S. trading partners, according to the Census Bureau.

No. 3 on that list is China, where the yuan is up a modest 3% since January 1. The rising economies of the Philippines and Colombia have experienced dollar-denominated appreciation of their respective pesos, while the Malaysian ringgit has also grown in value.

From the American perspective, though, the news is not all bad, or rather it’s as bad or worse for other countries. The South Korean won, Taiwan dollar and Indian rupee, local moneys of three more major trade partners, have remained fairly steady against the dollar. And currencies of nations where the economy is tethered to oil – Russia, Norway, South Africa – have all taken a pasting, according to information gathered via Yahoo Finance. (Persian Gulf states tend to peg their currencies to the dollar.)

The wonky part

So the foreign exchange (forex) market, which had been mostly tedious throughout the past decade, is suddenly a lot more volatile. And it’s not inconsequential. In April 2019, even before the current frenzy, $6.6 trillion was traded per day, including both spot transactions and derivatives, according to the Bank for International Settlements. That’s roughly 25 times the volume of all the world’s stock exchanges combined. Daily volume for 2020 are not readily available, but we’re willing to bet our last Venezuelan bolivar that it has gone way up.

These markets are driven in large part by interest rates. When a country raises the yield on its bonds, then it is in essence paying people more money to hold on to them risk-free. Money from abroad pours in to buy these bonds, or to be deposited in local banks which are now offering higher rates on deposits. This generates new demand for the local currency, which leads to a higher price for it. If a country cuts the yield, then the opposite happens, and it becomes cheaper to buy the local money.

Over the course of the pandemic-triggered recession, the Fed has kept interest rates as low as possible, so businesses can spend less on borrowing costs and more on buying things and paying employees. But this also means keeping money cheap. Of course, “cheap money” is just another way of saying “inflation.”

The Fed’s low-interest rate policy will end when the pandemic goes away and if, as appears to be the case, other developed economies emerge from the pandemic ahead of the America, then their currencies could continue to strengthen against the greenback. Viewed this way, exchange rates can be seen in this moment as the investment banks’ collective opinion of the order in which countries will return to normal.

How not to react

In the meantime, it will be cheaper for people in other countries to hire American workers or buy American goods, while it will be more expensive for Americans to acquire time and materials from abroad. That will only be solved once the Fed feels comfortable raising target interest rates again.

So, should we all go buy euros and pesos and ringgits, right? Not so fast.

Like any other investment vehicle, there are both fundamental and technical analyses to consider with every investment. But the forex market – worldwide, ‘round-the-clock, over-the-counter, and decentralized – is at once the world’s purest expression of capitalism, and it’s probably also the most confusing. The big banks and the hobbyist investor have access to the same data, but it’s the banks that have dedicated teams of analysts parsing those data. And it’s the bank that understands the Inside Baseball of the forex market.

And we didn’t even get started on cryptocurrencies, did we? These are digital tokens that serve as a medium of exchange in certain corners of the internet. They are issued not by sovereign nations but by technology teams which use cryptography to control the quantity available for purchase. Bitcoin is the first and most famous cryptocurrency, but there are hundreds of others. Some of them have inherent value in their ability to drive processes related to private companies’ databases, while others derive utility by supporting Internet of Things functions. Some offer a layer of privacy that goes beyond bitcoin’s capabilities. And others are only worth what speculators say they are.

Crypto is also a way of making anonymous transactions. This provides an on-ramp for engaging in deals that run from sketchy to downright criminal. But crypto is also the preferred medium for many people who simply take a libertarian view of monetary policy. These folks don’t believe that central banks serve a necessary purpose and believe that, whatever they happen to be buying or selling, it’s not the government’s business. Some crypto advocates also seek a store of value, untethered from a nation and its likely ballooning debt. Still, cryptocurrencies aren’t actual money, at least not yet. Who knows, maybe a decade from now we’ll all be using them at the farmers’ market.

No need to panic

There are more traditional ways of dealing with the current – and possibly sustained – downtrend of the dollar. The market for gold and other safe-haven precious metals is much less byzantine than that for forex and much more stable than that for crypto. Also, there are several funds available that hedge against inflation by investing in commodities or inflation-adjusted U.S. Treasury bonds. Or you could research which domestic companies receive the highest proportion of their revenues from exports or from operations abroad.

While these are challenging economic times, you have a dizzying array of investment possibilities from which to choose. So before you start parsing the difference between forex swaps and currency swaps – and there is a difference – maybe you should talk to someone who’s aware of the risks. If you’re not ready to dive that deep, it’s still advisable to talk to a skilled financial professional.